Metanomics: Building The Economy Of The Metaverse

Firstly, the term ‘metanomics,’ in relation to virtual worlds and the economy within, is something Doug Thompson was involved in more than a decade ago and ran a show within Second Life and a series of podcasts with the same name. I’d recommend checking them out because it’s all still relevant to where we’re heading today – I’m using it purely to frame where things are likely to end up in a metaverse context because it’s a cool word.

In 2010, a night club within the game Entropia Universe was sold for $635,000. The virtual equivalent of Amsterdam was sold in Second Life for $50,000 in 2007. An elf called Zeuzo was sold in World of Warcraft for $9,500 that same year. A 21-year-old earned $125 for controlling someone’s identity for an hour, and a 16-year-old won $3 million in prize money in the Fortnite World Cup.

Want another example?

Some ingenious players created a bank in EVE Online back in 2009 called the E-Bank. They basically created a Vostro account system, similar to what already exists in central banks in the real world. They were issuing loans, paying interest, they had a CEO, a board and it was extremely well organized. Then the CEO robbed it of 200 billion ISK (the currency of EVE) and swapped it into over 6,000 Australian dollars.

This is metanomics – the economy of the metaverse – and it’s happening all around us right now.

2.5 billion people are interacting through their phones, consoles, laptops, desktops, and VR headsets all in virtual environments, living and trading money online. We are witnessing something which will very well affect society and economies in real life, blurring the lines between both worlds. What happens in one will affect the other, billionaires will be made and corporations bankrupted. The pandemic has been a real litmus test of just how intrinsically linked the two worlds are – metanomics is an asymmetric hedge against real-world events. When things go well, so too does the virtual economy but when things go south, it can shine as a destination for entertainment and community, completely autonomous without interference from the outside world.

Right now the buzz is all around the creator economy, NFTs (non-fungible tokens), and the distributed ledger-based exchanges that allow people to buy, sell and trade. The NFT market volume is apparently trading over $700 million and OpenSea is heading for a $100 billion valuation in record time. Etherium blockchain-enabled marketplaces appear to be winning as a strategic infrastructure that will support metaverse economies, but right now there’s something missing.

There is a lack of utility and a lack of connected economies.

People access markets for virtual gaming goods for many reasons. According to Vili Lehdonvirta, a digital economies specialist from the Oxford Internet Institute, users typically buy digital goods for the same reasons they purchase physical goods: status, recognition, and affiliation to specific subgroups and communities. This is why NFT marketplaces like Exclusible exist – to tap into the status of owning a prestigious brand NFT from a top fashion house rather than a Cryptopunk – you have that affiliation and status with luxury and within that community. The metaverse represents the opportunity to create diverse communities that mirror the real world.

Digital goods are being bought and sold, it’s a speculator market out there but there is not much more to do with what you own. To create functioning economies in the metaverse you need to be able to do something with your ownership. If I buy a freshly minted dining table in a marketplace I want to be able to furnish a virtual home with it. Right now all I can do is admire my purchase on OpenSea or some other site and tell everyone the URL. There is nothing to do….currently. The lack of open utility right now (this doesn’t include buying goods within the walled garden of another metaverse because that’s what they’re meant for) will be an issue for a number of years to come, especially as the industry itself wrangles with the problems of standards and interoperability. Epic Games’ Tim Sweeney reckons we’re in for at least 5-10 years of pain on that front and, frankly if true, the delay is likely to kill virtual economies stone dead.

On top of this, the promise of distributed ledger-based exchanges and the proliferation of different altcoins that power them should mean that the transfer of the value of goods and services across different metaverse will be easy.

But we are very far from realizing this dream.

It’s reminiscent of the days of startups creating ICOs as a means of crowdfunding their business. We have different virtual worlds being spun out with their own token-based economies but no real connected exchange of value or assets into other realms. My plot of land in Decentraland might be completely worthless if I want to trade it for a plot of land in Ember Swords for example. Similarly, the mechanisms for buying, selling and trading through exchanges requires a certain level of understanding of cryptocurrencies and using Metamask, for example. Altcoins need to be converted into Etherium or another more recognized cryptocurrency, then back again into the altcoin of another metaverse in order to exchange – each time incurring a fee. We’re in the infancy of a functioning exchange market that’s as accessible as fiat, but one that cuts out a large number of people who want to participate in the metaverse but don’t understand how metanomics works.

This is especially true when you consider that people set up eBay stores to trade in digital goods and rare items, another touchpoint where the two worlds collide. If you cannot openly trade virtual wares in the real world, there is little utility.

The other side of the problem is demand and supply.

What I mean is, for functioning economies we need to think about consumption, destruction and scarcity of resources.

The theory behind it is that, if I purchase a virtual good with my virtual currency – I’ll use an example of a rare online schoolhouse that remains on my game board within a game, and I purchase it for five dollars – the theory behind it is that, as a user, although the terms of service may, in fact, state that the social-gaming company has no obligation to the user after that transaction occurs, the fact of the matter, as a user, when I log in tomorrow, into the game, it is my expectation that that schoolhouse will be there, and it’s my expectation that that schoolhouse will continue to be on my game board for as long as I continue to play the game. By the same token, if I purchase something such as virtual fuel for my virtual vehicle, the revenue really doesn’t get earned until you use the virtual fuel for your vehicle, until it’s consumed. So the basic model is that you recognize revenue on the sale of virtual goods, not on the sale of virtual currency. But at the time that the virtual currency is converted into a virtual good, revenue recognition commences, and you recognize durable items over its estimated useful life, and consumable items, such as the virtual fuel example, as it’s consumed.

– Michael Bobroff

This is more in line with MMO video game economics but it has a real part to play in moving the metaverse experience along. There is a purpose beyond just a social construct: people will be driven to create using the resources within the metaverse they choose to live in, just like a functioning economy in the outside world.

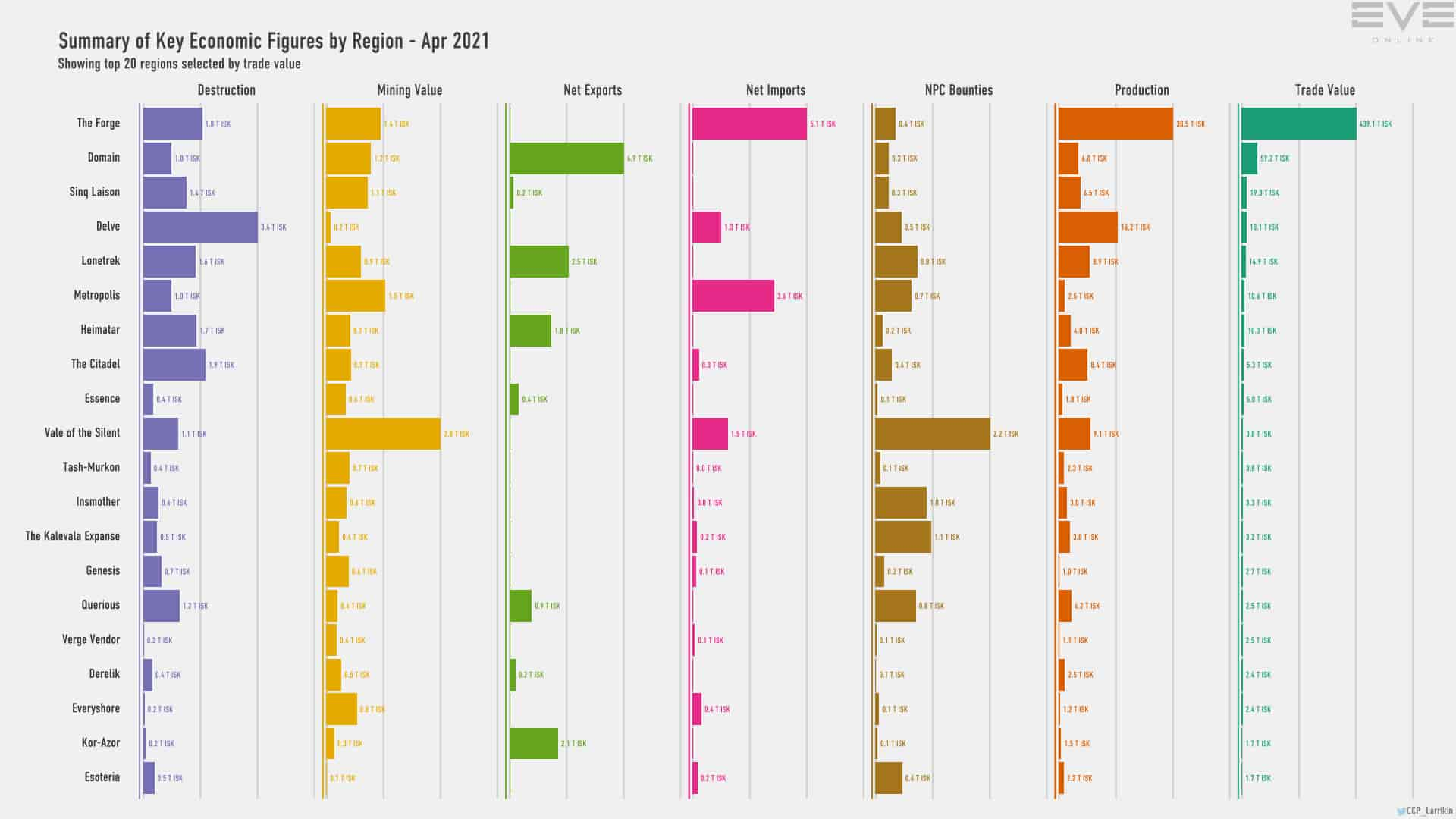

I’ve said it many times before and I’ll repeat myself again: EVE Online is probably the best example of a functioning economy in a virtual environment. It beats Second Life hands down. It’s a video game first but definitely a metaverse second.

The EVE Online market is managed and led by Dr. Guðmundsson and his team of economists. They designed the market such that there is an unlimited amount of material to be collected throughout the virtual universe it’s set in. However, collecting materials takes time and resources. In other words, there are always opportunity costs and trade-offs for collecting materials. Due to these trade-offs, materials collected gain value.

The in-game economy in Eve Online is an open economy that is largely player-driven. Non-player character (NPC) merchants sell skill books used by players to learn new skills and blueprints to manufacture ships and modules. Players mine resources, create new goods, exchange virtual cash for services and create contracts. There is a highly functional political system in EVE between groups of players and the factions they belong to.

NPC merchants also buy and sell trade goods – this is something that really sets apart the game but also as a concept for metanomics – that AI-driven participants continually drive forward the economy too.

The evidence suggests that EVE adheres to real-world microeconomic assumptions. It appears that game theory and auction theory are both testable mediums in EVE. Furthermore, the data show a relationship between supply and demand that are accurate according to microeconomic theory.

– Christopher Smith, UW Oshkosh

EVE Online may be an anomaly, but it’s been studied by economists for years who want to understand just why it functions so well. While EVE doesn’t have some of the concepts mentioned earlier, like material decay or scarcity, they are attributes if introduced to a metaverse could very well drive the metanomics of the virtual world it’s set in.

You can give EVE players a shovel and expect them to maybe dig a hole and instead they’ll take that shovel apart and make a hammock out of it.

– Peter Farrell, community developer, CCP Games

Star Wars Galaxies is another standout example of a player-driven open economy that allows the creation of assets to the point that many were unique – much like the NFT market, we’re seeing today. In a previous blog, I wrote about how a distributed system could allow the creation and registration of new items that consumed resources within the metaverse and that blueprint could act as a license and means of generating revenue for the creator to sell to others. That in turn would create a reseller market or a means of production that consumed resources, employed people to create the goods and sell them…

If the metaverse sounds too much like the real world, in a sense some of the virtual worlds we’ll see evolve will become as highly functional and people will live and make money there rather than on the outside.

Metanomics represents a real opportunity within the metaverse. We’re at the early stages of understanding how rich and vibrant economies can be run within these virtual worlds and how each can potentially affect not only the other but the outside world too.

Oh, and don’t think the tax system isn’t paying attention. With this much money at stake you can bet your NFTs that regulation will fast catch up to virtual economies and the transfer of wealth in and out.

But if it takes a team of economists to run the economy within just one game, this also gives a glimpse of the hurdle facing each metaverse owner trying to set up a functioning economy within their world too – and we need to think about this beyond simply setting up a crypto-exchange for NFTs.

Theo Priestley is a leading tech futurist and globally recognised public speaker, best-selling author on artificial intelligence, spatial computing and the convergence of trends towards the metaverse. He is the founder of Metapunk, an advisory service on how to navigate the metaverse revolution.

Theo Priestley is a leading tech futurist and globally recognised public speaker, best-selling author on artificial intelligence, spatial computing and the convergence of trends towards the metaverse. He is the founder of Metapunk, an advisory service on how to navigate the metaverse revolution.