Moore’s Law continues to carry on. It has defined the pace of computing advancement for the past five decades — everything from PCs to mobile devices to flat screen TV’s. And it will do the same for XR, sort of.

As background for those unfamiliar, the law was devised in 1965 by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, who asserted that the number of components you can fit on a chip doubles every year while the price halves. It’s been revised a few times since then, but has sustained conceptually.

The size/cost function is generally why technology shrinks in price and size over time. And it’s what we in the analyst corps use in part to project XR penetration. For example: when will AR glasses get sleek and cheap enough to pass stylistic requirements for consumer-markets?

But there’s one limitation in how far the law can take us: the physical bounds of matter itself. Because it hinges on size, it’s limited by the how small things can get. And of course, there’s a physical floor on chip components getting smaller when we get into atomic ranges.

Beyond Silicon

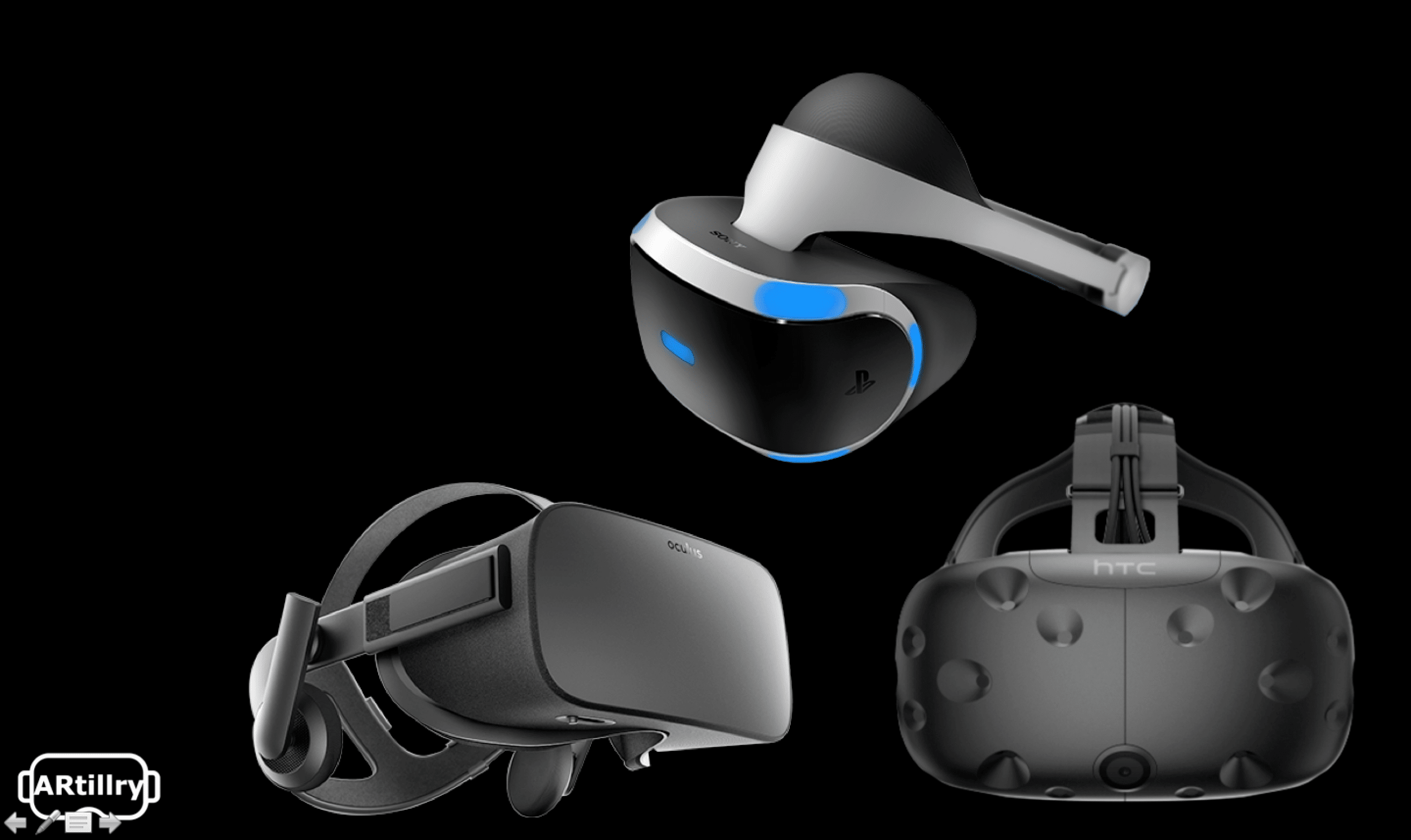

One XR authority has been vocal about this impending challenge: John Carmack. The Oculus CTO is generally an impassioned voice on several technical issues in VR, and this is one of them. He believes that Moore’s Law only has a few more cycles before we hit that physical limit.

“We are running out of Moore’s Law,” he said in a WIRED interview. “Maybe we’ll see some wonderful breakthrough in quantum structures or whatever, but if we just wind up following the path that we’re on, we’re going to get double or quadruple, but we’re not going to get 50x more powerful than where we are right now. We’ll run into atomic limits on our fabrication.”

He’s technically correct, but it’s a question of if we live by the spirit or the letter of the law. The letter of the law will bring us the day Carmack suggests. But squinting at Moore’s Law with more optimistic eyes could reveal possibilities for unforeseen inflections or new discoveries.

“I was sitting in the audience when [Carmack] said that at OC4,” Nvidia’s Martina Sourada told ARtillry during a panel discussion last fall. “But I believe there could be advancements we haven’t seen yet that will extend our capabilities, such as discovering materials beyond silicon.”

Sweet Spot

The two sides come together in the notion that we should always optimize software design for the tools we have, and not rely too heavily on those that the future may or may not afford. For example, Carmack advocates optimizing apps to the limits of the hardware, like Oculus Go.

“Some of [my favorite VR experiences] are clearly very synthetic worlds where it’s nothing but cartoony, flat-shaded things with lighting but they look and they feel good,” he said. The lesson: a low-poly approach is better if it works, versus intensive graphics that the device can’t handle.

But it goes beyond graphics or other specs-driven decisions. It’s about deeper product strategies and design tradeoffs. After using Oculus Go for example, it’s clear to us that successful apps will excel at simple/casual game mechanics or lean-back entertainment — Go’s realistic sweet spot.

Wherever we are in the course of Moore’s Law or in XR’s lifespan, there will always be more advancement coming next. So at any given point, it’s about optimizing for the current toolset while also triangulating what the next ones will afford… and get there first. Of course, it won’t be easy.

For deeper XR data and intelligence, join ARtillry PRO and subscribe to the free ARtillry Weekly newsletter.

Disclosure: ARtillry has no financial stake in the companies mentioned in this post, nor received payment for its production. Disclosure and ethics policy can be seen here.