Hey everyone, I’m Stef, and I’m a user experience research (UXR) lead at Meta, focused on emerging products — in particular, augmented reality (AR). Before starting this career, I was a psychology grad student, who could only foresee one feasible path toward a profession:

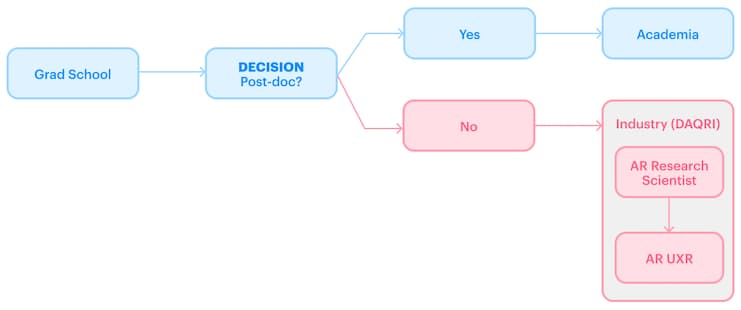

I completed my Ph.D. in 2015. At that time, I did not know UXR — never mind AR UXR — was a career option.

How did I end up here?

Making the leap: translating academic skills into UXR-speak

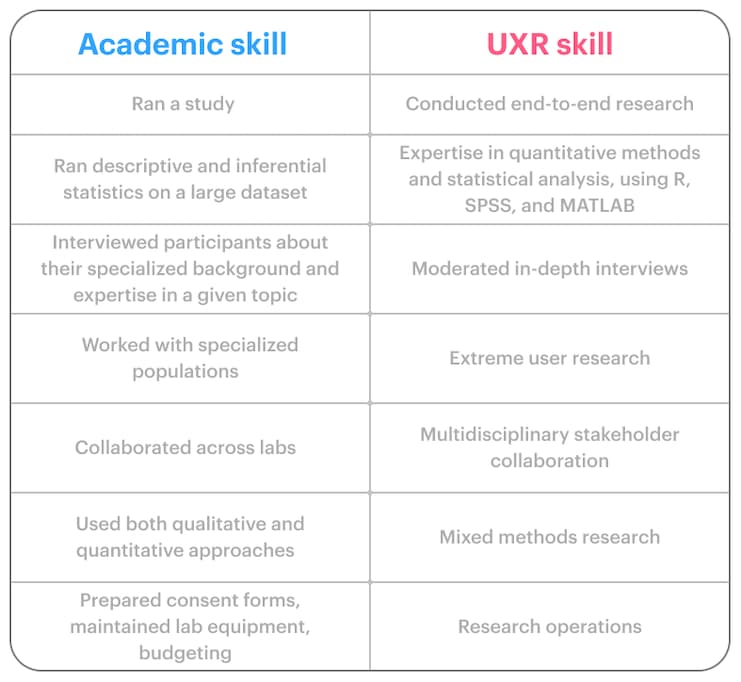

Like many academics, my days in grad school were filled with designing and running experiments. This included writing surveys, recruiting participants (in my case, musicians and people with specialized language skills), collecting and analyzing the data, and presenting reports. I would collaborate between labs and handle operational aspects of research, like preparing consent forms, maintaining lab equipment, and budgeting for my studies.

I still do a vast majority of these things as an AR UXR, but I just call them something different. This translation process was one of the biggest challenges to overcome when transitioning into the industry. With these years of hindsight, I put together a cheat sheet of “how to talk UXR”, that you can use when putting together your industry resume.

Now that you can talk the talk, learn to walk the walk

You will need to adapt some of your academic skills when transitioning to a UXR role. My three main lessons for successful adaptation are:

Rigorous research is table stakes

In academia, we spend a lot of time talking about methods. Methodological rigor is a key yardstick against which your research excellence is measured. In industry, knowing your methods is a given. For years, I expected someone would ask me a hard question about my methods. It never came. Save for key information like sample size and my method of choice, my methodological details now live in my report appendix. UXR, unlike academic research, is conducted to help the team develop a strategy or make a decision. As such, my industry audience wants to know the “so what?” factor of my research. They trust I’ve done everything properly on the backend.

Learn the art of accurate storytelling

In order to make these “so what?” insights stick, I need to tell a story about my research to my product stakeholders. This story wants to motivate the team to act on the findings. Storytelling does not mean you embellish your findings. It is your responsibility to accurately distill your core messages for your audience. The eventual narrative still stands on original, rigorous research, even if that lives more in the background now.

UXR is a team sport

Earlier, I mentioned that UXR helps product teams make good business decisions. This means you need to work closely with your team (many of whom are unlikely to have a research background) to understand business context, and the decisions they need to make. To become relevant, your research will need these inputs.

Do I need a Ph.D. to become a UXR?

No. Though I gained my foundational research skills through a Ph.D. program, it doesn’t need to be this way for you. In fact, the more backgrounds we have represented in UXR, the better. PhDs are often listed as “nice-to-haves” on job postings, as it is evidence of a demonstrated research track record. However, a PhD is typically not a requirement, as long as you can demonstrate a rigorous research background, storytelling, and collaboration skills.

The AR part

My first role out of grad school was as a research scientist at an AR startup called DAQRI.

I found this role by looking for an opportunity where I could share what was unique about my background. I completed my PhD in a specific branch of psychology called auditory cognitive neuroscience. Specifically, I studied how our brains make sense of our environments, focusing on sound perception. I used a method called electroencephalography, which records electrical activity on the scalp of a listener. This background, unbeknownst to me during grad school, made me a good fit for a BCI-focused industry research role.

On the job, I quickly learned that AR content is inherently spatial. I started to see another throughline to my background: the increasing number of sensors on AR hardware meant that these devices were starting to mirror our perceptual system, making sense of our environments. I realized that I could apply my understanding of how we perceive our environment and could inform how we design and interact with AR technology!

My years of multidisciplinary stakeholder collaboration also proved useful, spending time with one foot in the R&D lab, and one foot on the product team. I would often collaborate with product designers on writing up patents on sci-fi-sounding ways to use BCIs as user inputs for AR headsets [1, 2, 3]. After many late nights in front of whiteboards, I learned about our team’s near-term challenges. The designers were trying to understand how to best display things we take for granted, like browsers or menus, in this new medium of AR. Hey, I’m in the business of hypothesis testing, I told myself – maybe I can help them out.

On the recommendation of one of my designer-collaborators, I ordered Goodman & Kuniavsky’s Observing the User Experience (2012). Reading its opening pages, I discovered an entire field that lay parallel to everything I had studied. It was called UXR, the study of customer goals, motivations, and unmet needs to inform product development and business strategy.

A week later, with my newfound learnings, I ran my first concept test. Then I ran another, and another, and so it went, until I established the UXR function at the company, and started to train others in what I had learned. From there, I went on to lead UXR for several AR and 3D product launches at Adobe, and most recently, joining Reality Labs to work on defining the next generation of AR user experiences.

Do I need a technical background to work in AR UXR?

I’m often asked if I specifically studied AR, or certain technologies central to AR, such as computer vision. No – everything I learned about AR, I learned on the job. I did this by immersing myself in materials to hone my AR industry knowledge. This immersion has helped me better communicate with my stakeholders in AR product, design, and engineering.

I regularly read about tech happenings on TechCrunch, have a Google Scholar alert for “augmented reality user experience”, and regularly visit ARtillery Intelligence for AR/VR-specific market research insights. In addition, I regularly attend (and have presented at) the Augmented World Expo industry conference.

It has also been important to me to experience AR, such as by getting hands-on with AR creation tools (like Spark AR Studio). This experience has helped me think critically about product decisions, form points of view, and communicate with my research stakeholders.

3D is also inherently a part of AR experiences. Spending time with a free 3D tool like Blender, can help you learn 3D basics (with the help of YouTube tutorials). I couldn’t finish this section without saying that I do think reading up on the basics of human perception is also useful when thinking about the types of design challenges you might face in AR UXR.

Focus on people, not technology

What has served me equally well as reading up on AR is continuing to hone my UXR craft. People change a lot less quickly than technology. Even in AR UXR, we’re still in the business of understanding people and their needs.

General UXR resources I’ve referenced throughout the years:

- Jeff Sauro’s blog, Measuring U: A resource that taught me how my statistical training could be applicable in product development.

- Jordan’s Business Anthropology (2013): The book that taught me about the rich history of anthropological methods in business settings.

- The researcher’s journey, leveling up as a user researcher, 2017 Medium post by Dave Hora: A valuable glimpse at the difference between an entry-level versus senior researcher.

- Industry conferences and their resources, such as EPIC (their tagline is “advancing the value of ethnography in industry”) and UXR Conference.

- IDEO’s Advanced Design Thinking Certificate, which taught me to let go of academic perfectionism, and work according to the design-test-iterate loop.

- Dunne & Raby’s Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, which taught me about future thinking.

In conclusion: my departure from academia is not an anomaly. In fact, people leave for all sorts of reasons. According to NSF’s 2019 survey of Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities, only 52% of doctoral recipients in social sciences had secured a job in academia (excluding post-doc positions).

Regardless of how you leave academia, chances are you will have a vertigo moment like me, when considering departure. From my entry into a specialized psychology undergraduate research program, right up until the last conference I attended in my Ph.D., the messaging was clear: you will go to graduate school, and then you will pursue a professorship. When life events prodded me to peer over the precipice into “industry jobs”, the view was terrifying. What, if any, of my academically-minded skillset was valuable? Where would I even apply them?

Though you now know that the answer was, “yes, as an AR UXR”, it was a long journey. The less obvious part of this transition was my loss of academic researcher identity. Academic research is what I did all day, every day, including nights and weekends. I remember sitting in the kitchen on Christmas in 2012, analyzing data. Most of my social circle revolved around academia. This meant that my identity was wrapped up in being an academic researcher.

Furthermore, academic mentors use both overt and subtle messaging to groom the next generation of themselves. A path into industry, however, in addition to corrupting intellectual purity, would erode methodological rigor and stain a publication record.

So, why did you leave?

I almost didn’t. I had a postdoc lined up in Finland, but personal circumstances pulled me to a Silicon Valley job search. My partner, who worked in tech, was about to move to California. I wasn’t thrilled about being 5,435 miles away, so started the job search on the West Coast.

Through my partner, I had gotten a taste for tech, leaving me with a nagging feeling that there was something else out there. I knew what academia had in store for me. That misgiving, combined with a growing interest in early virtual reality headsets (in particular, Crescent Bay – with spatial audio capabilities relevant to my subdiscipline of auditory cognitive neuroscience), solidified the decision.

Stefanie Hutka is a user-experience research lead at Meta, focusing on emerging products. Follow her on Twitter at @StefanieHutka. A version of this article first appeared on the Spark AR Blog, published here with permission.

Stefanie Hutka is a user-experience research lead at Meta, focusing on emerging products. Follow her on Twitter at @StefanieHutka. A version of this article first appeared on the Spark AR Blog, published here with permission.